An Ongoing Fight for Educational Equity

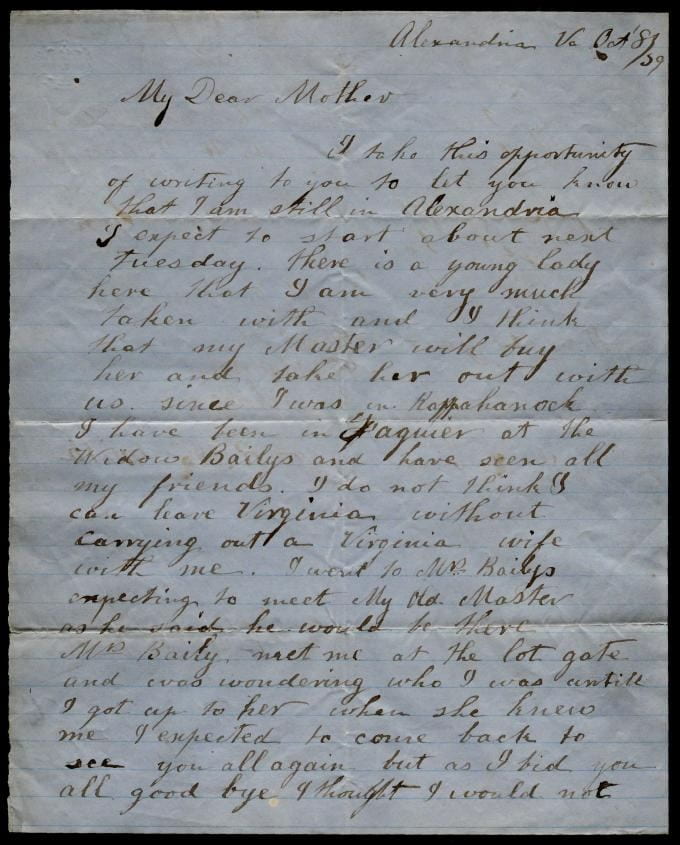

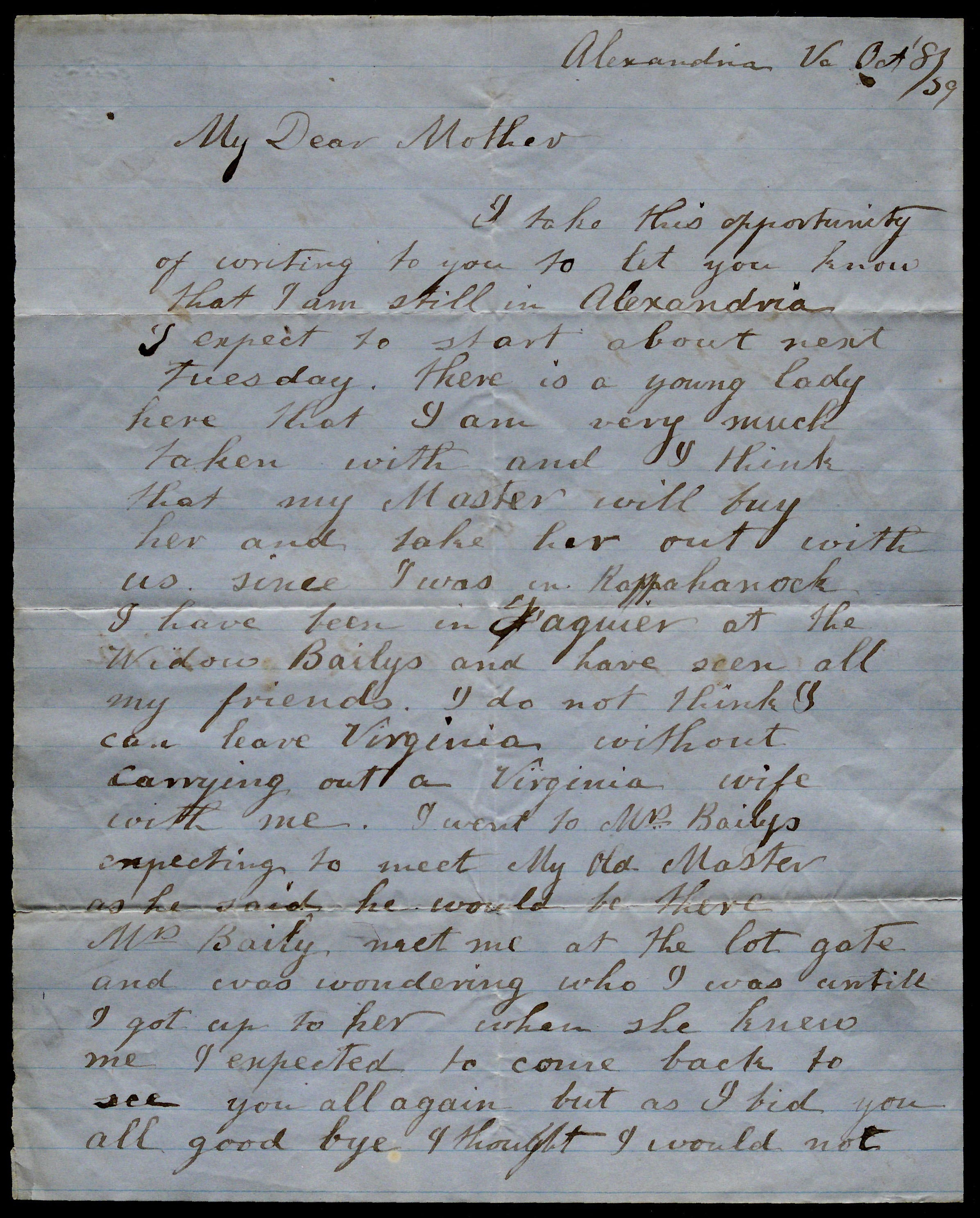

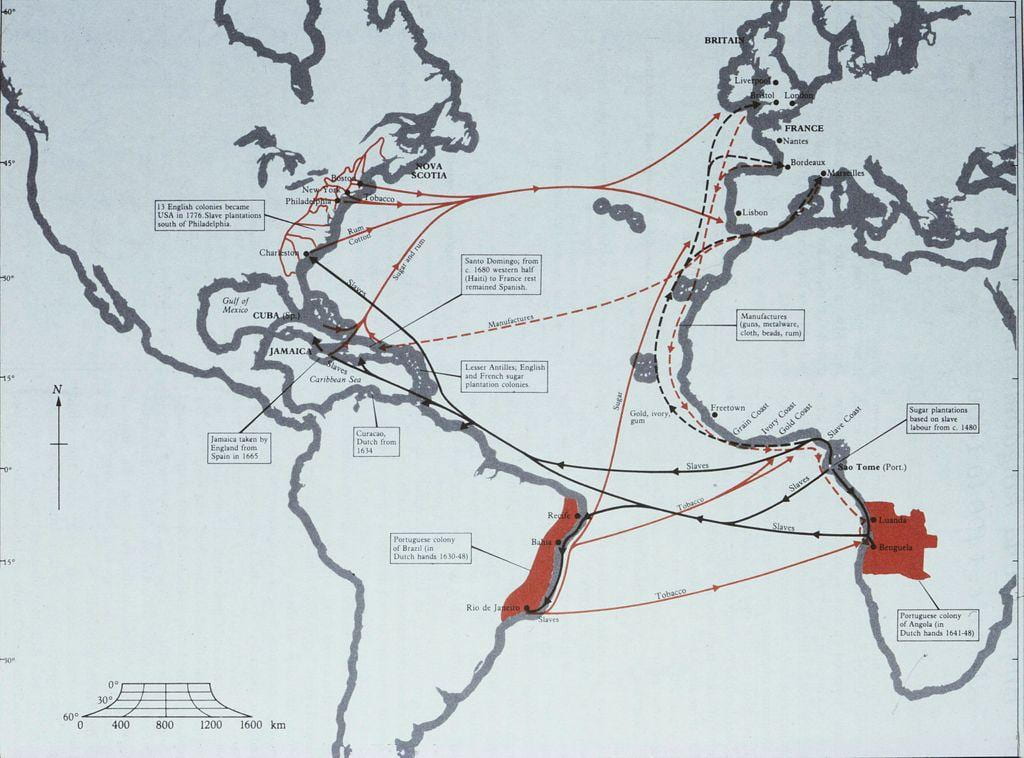

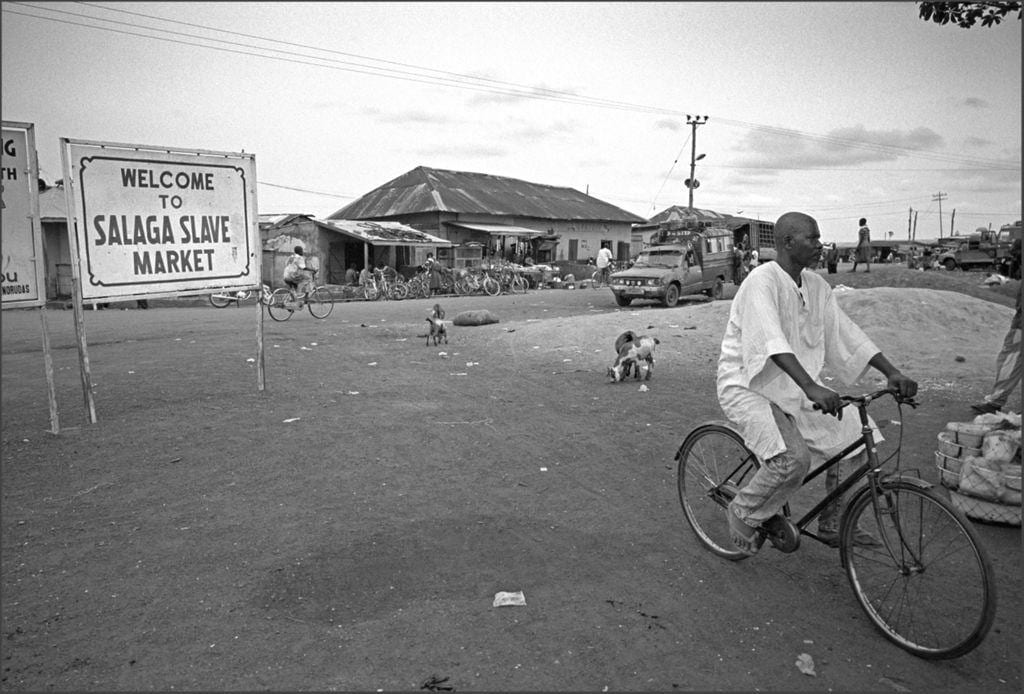

Post emancipation, the struggle for educational rights did not end within the Black community. For recently freed African Americans, literacy was a crucial first step in independence and self-sustainability. Education established African Americans as civic members of society, opened up employment opportunities, allowed for wealth accumulation, enabled property ownership, and most importantly was necessary for protecting freedoms and rights. However systemic racism and socioeconomic hardships has left the African American education system weak and the fight for educational equity continues even today in the 21st century.

The Evolution of African American Education: Challenges of Reconstruction and Jim Crow

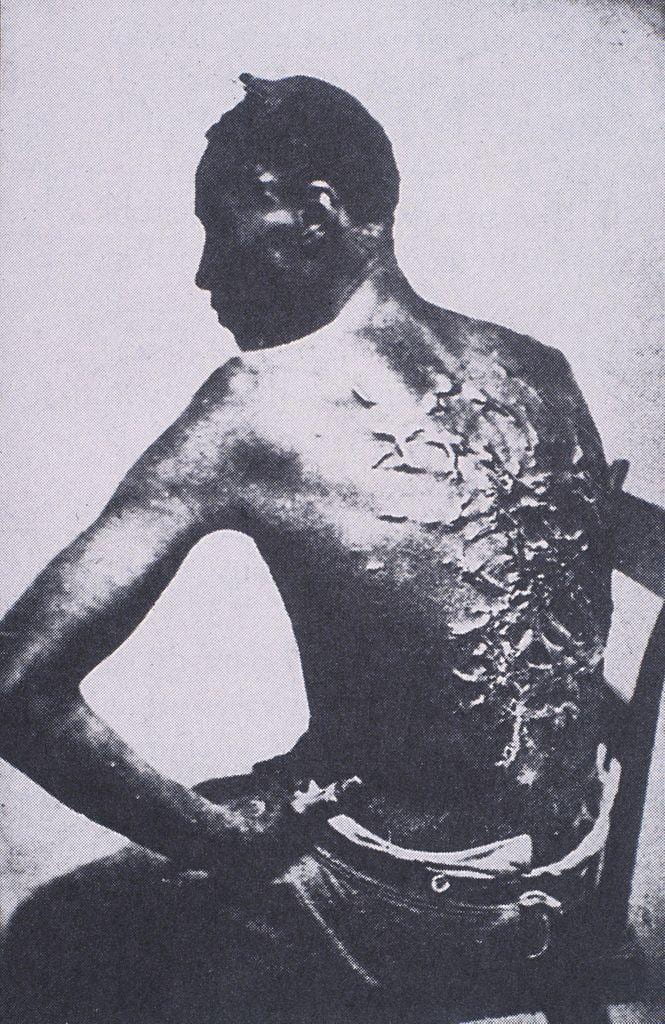

Immediately after the end of the Civil War during reconstruction, educational opportunities for African Americans remained low due to the lack of qualified teachers and economic limitations. Many African American communities could not afford to pay teachers, and individual families often did not send their children to school because they needed them to work for a wage. With the end of reconstruction and the beginning of the Jim Crow era, new challenges were faced by African Americans trying to get an education. In 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson, a landmark supreme court case, ruled in favor of the “separate but equal” doctrine, protecting Jim Crow Laws and the continuation of racial segregation in America (Library of Congress). As a result, schools remained segregated. During this time, African Americans were not granted the same educational opportunities as their White counterparts. African American schools were fewer and more widespread, making educational access limited, and the institutions that did exist were commonly underfunded. However, despite all barriers African Americans continued to recognize the importance of education and fight for it as a right. As said by Booker T. Washington, “If you can’t read it’s going to be hard to realize a dream.” Booker T. Washington was an advocate for education within the Black community and regarded education as a means of “lifting the veil of ignorance” (National Museum of African American History and Culture).

Segregation of facilities upheld by ruling Plessy v. Ferguson (“History, A&E Television Networks”).

Empowerment of African Americans Through Education

In the almost 40 years after emancipation prior to 20th century, over 90 higher education institutions were founded exclusively for African Americans in the wake of segregation. These schools, referred to as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), promoted enlightenment and self-discovery that was previously denied to African Americans and enslaved individuals. HBCUs also acted as a protector of African American history, culture, and traditions, ensuring that these were passed down from generation to generation. While there were flaws in the argument for Black Colleges and Universities, overall these institutions were a victory in the ongoing battle for equal education rights in the Black community and helped pull many African Americans out of a cycle of impoverishment by providing them with the skills, experiences, and networks necessary to establish a successful career (National Museum of African American History and Culture).

Charlotte Hawkins Brown: A Pioneer for African American Education

Because education has consistently been seen as a form of freedom to the descendants of enslaved and formerly enslaved people, Black Americans have long fought for equal access to education and recognized its value within their communities. An example of African Americans’ resilience to educational oppression is seen through the life work of Charlotte Hawkins Brown. Brown, the descendant of slaves who dedicated her life to education and learning, opened a school for middle class Black children in 1902, in Sedalia, North Carolina (Hornsby-Gutting, Wilson, 300). Brown’s school was one of the most distinguished learning institutes for African Americans during the time period and was innovative in its teachings. Over the course of its operation the school evolved from predominately vocational learning to a liberal arts curriculum that prioritized math, science, history, and literacy. This was deviation from what was considered a typical education for African Americans in the United States at the time (Hornsby-Gutting, Wilson, 300). Brown led a life advocating for the educational freedom of African Americans in rural North Carolina, and used her intelligence in the continued fight for equality during the Jim Crow Era.

Education pioneer Charlotte Hawkins Brown (“The First Lady of Social Graces”).

The Impact of Systemic Racism and Socioeconomic Disparities on Education Inequality

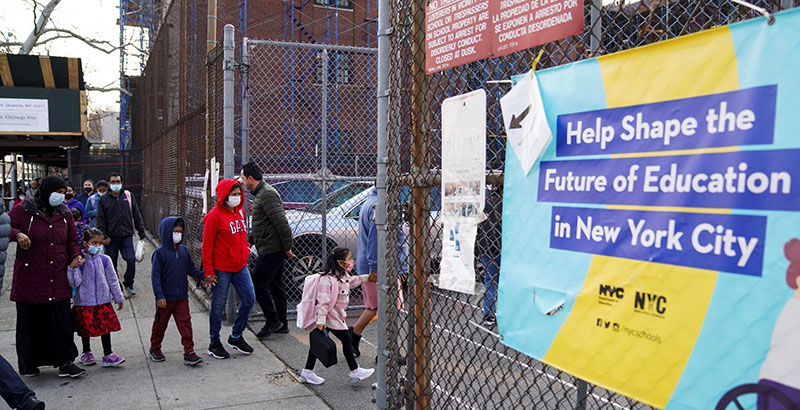

Despite the fight for educational rights both pre and post emancipation, slavery has left a legacy of racial disparity in the U.S. education system that is perpetuated by gaps in socioeconomic status between White and Black Americans today. This means that for African Americans the battle for educational equality is ongoing. Today, unequal distribution of resources, implicit bias, and generational wealth gaps create educational disparities in the Black community. Despite the integration of schools in America over 50 years ago, many public schools today remain ethnically and racially isolated due to the district system and economic barriers. In 2024, 58% of Black students in the U.S. attended schools where over 75% of their classmates shared their race or ethnicity (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). Many of these schools, located in areas that are predominately Black and have higher rates of poverty, are underfunded meaning that there is a lack of current textbooks, updated technology, school supplies, and high-quality administrators. In fact, African Americans in the U.S. experience some of the highest poverty rates, second only to Native Americans (Kaiser Family Foundation). These economic obstacles further exacerbate educational inequality in the 21st century. The Economic Policy Institute found that while less than one in three white students attended a high-poverty school in the U.S. more than seven in ten black students did (Garcia). As a result of the discrepancy in education quality, 84% of Black students in America read below their grade proficiency level and 91% tested below their grade level for math (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). This statement highlights how systemic inequities in education disproportionately affect Black students and their academic outcomes.

Students protesting against inequality in the U.S. education system (McCann, 2020).

We also see that Black students are more likely to face disciplinary action in school than their White counterparts. Across America Black students have high rates of suspension and expulsion. While this can lead to disengagement in the classroom and academic struggle it also doubles the risk of high school dropout. On average, only 81% of the nation’s Black students graduate from high school (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). This statistic is significant not only because a high school diploma is required for almost any job in America, but also because dropping out of high school triples a student’s risk of incarceration or involvement with the U.S. justice system (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). This shows how racially biased disciplinary practices create widespread consequences for Black students in the U.S. and perpetuate a cycle of educational inequity.

Integrated schools in the U.S after Brown v. Board of Education ruling (Romeu and Pineda, 2021).

In 2017, The Economic Policy Institute conducted a study which found that socioeconomic status is one of the most influential factors in academic success. Extensive research showed that the development of cognitive and social skills early on in life shapes the future success of an individual and the underdevelopment of these skills leads to “lowered economic prospects later in life”(García and Weiss). However, because predominantly Black schools in America are underfunded and lack appropriate resources, the growth of these crucial skills is often stunted. A national study notes that children with low socioeconomic status are on average 5 years behind the literacy skills of their high-income classmates (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). Without access to adequate primary education, students are less likely to get a college degree. The same study found that children with a high socioeconomic status are 8 times more likely to graduate from college than children with a low socioeconomic status (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). Without a higher education individuals are subject to lower salaries and often get stuck in low-income demographics. As a result of their economic status, their children are less likely to get a proper primary education and go on to attend college. The Center for Education Policy Analysis at Stanford University notes, “Black and Hispanic children’s parents typically have lower incomes and lower levels of educational attainment than white children’s parents. Because higher-income and more-educated families typically can provide more educational opportunities for their children, family socioeconomic resources are strongly related to educational outcomes” (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). Thus, a cycle of poverty, low socioeconomic status, and below-average education levels is perpetuated and passed down from generation to generation (García and Weiss).

Depiction of an inner city school in New York. These institutions that have historically been racially isolated and underfunded (Jacobson, 2022).

Addressing the Legacy of Slavery in Educational Inequity

Slavery has left a profound and lasting legacy on the United Sates, shaping both the social and economic fabric of our society. The impact of slavery, compounded by the racist systems that followed, continues to affect African Americans everyday. Racial inequality persists, creating generational challenges that are near impossible to overcome, especially in the realm of education and socioeconomic status. Because of the dark stain of slavery and racism on our nation, conscious, continuous efforts must be implemented in order to mend deep-rooted inequities.

One way that Virginia is working towards educational equality in the wake of slavery is with reparations. Educational reparations which provide financial aid and scholarships to universities in Virginia for African American students are one way that the state is trying to educate and repair a society broken by the legacies of slavery. In 2021, the previous governor of Virginia Ralph Northham signed a piece of legislation outlining the establishment of the Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Programs (Bromley). Bomley states, “[The bill] requires five public universities that were established before the end of the Civil War and used enslaved laborers to build their institutions to address their history with slavery, including searching for enslaved individuals and their descendants. They are required to make reparations through scholarships or community-based economic development and memorial programs, starting in 2022” (Bromley). These educational reparations don’t right the wrongs of slavery and institutionalized racism in the United States, but they are a step towards taking responsibility for them and acknowledging the lasting effects of slavery that are still felt by African Americans today. While reparations hold potential for addressing educational inequities stemming from slavery and racism, they are only a small step. Ongoing policy changes and sustained efforts are needed across the nation to achieve meaningful, lasting progress.

University of Virginia signs document that focuses on reparations for descendants of enslaved workers (Bromley, 2021).

Then and Now: Breaking the Cycle

The legacy of slavery and the deep-seated systemic racism that followed it continues to shape educational opportunities for Black Americans today. Despite advancements in African American education, such as the establishment of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and the work of pioneers like Charlotte Hawkins Brown, inequality remains prevalent, particularly due to socioeconomic disparities and racial biases in the U.S. education system. While efforts like reparations in Virginia offer a glimmer of hope, they represent only a small part of the larger solution needed to address generational educational inequities. Permanent change will require continued, comprehensive policy implementation and sustained commitment to break the cycle of disadvantage and ensure equal access to quality education for all. Only through these ongoing efforts can we hope to close the gap created by centuries of enslavement and systemic oppression.

Sources

Baker, Regina S. “The Historical Racial Regime and Racial Inequality in Poverty in the American South.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 127, no. 6, May 2022, pp. 1721–81, https://doi.org/10.1086/719653.

Bromley, Anne E. “New Law, Signed at UVA, Focuses on Reparations for Descendants of Enslaved Workers.” News.virginia.edu, 5 May 2021, news.virginia.edu/content/new-law-signed-uva-focuses-reparations-descendants-enslaved-workers.

DevTech Systems. “Racial Integration of Schools in the United States.” DevTech Systems, 26 Feb. 2021, https://devtechsys.com/insights/2021/02/26/racial-integration-of-schools-in-the-united-states/.

Franklin, V. P. “Introduction: Cultural Capital and African American Education.” The Journal of African American History, vol. 87, 2002, pp. 175–81. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1562461. Accessed 23 Jan. 2025.

Garcia, Emma. “Schools Are Still Segregated, and Black Children Are Paying a Price.” Economic Policy Institute, Economic Policy Institute, 12 Feb. 2020, www.epi.org/publication/schools-are-still-segregated-and-black-children-are-paying-a-price/.

Harris, Danae. “68 Years After Brown, Schools Still Highly Segregated: 4 Takeaways from Study.” The 74 Million, 17 May 2022, www.the74million.org/article/68-years-after-brown-schools-still-highly-segregated-4-takeaways-from-study/.

History.com Editors. “Plessy v. Ferguson.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Oct. 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/plessy-v-ferguson.

Hornsby-Gutting, Angela, and Charles Reagan Wilson. “Brown, Charlotte Hawkins: (1883–1961) ACTIVIST AND EDUCATOR.” The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 13: Gender, edited by NANCY BERCAW and TED OWNBY, University of North Carolina Press, 2009, pp. 299–301. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469616728_bercaw.80. Accessed 23 Jan. 2025.

Kaiser Family Foundation. “Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 4 Dec. 2019, www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22.

Library of Congress. “Plessy v. Ferguson: Primary Source Set.” Chronicling America, https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-plessy-ferguson#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Supreme%20Court%20changes,for%20the%20next%20fifty%20years. Accessed 23 Jan. 2025.

McCann, Róise. “Student Protest Exposes Inequality in the Education System.” Socialist Party, 21 Sept. 2020, www.socialistpartyni.org/analysis-news/local/student-protest-expose-inequality-in-the-education-system/.

National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Emancipation and Educating the Newly Freed.” NMAAHC, Smithsonian Institution, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/emancipation-and-educating-newly-freed. Accessed 23 Jan. 2025.

National Park Service. “African Americans and Education during Reconstruction: The Tolson’s Chapel Schools.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/african-americans-and-education-during-reconstruction-the-tolson-s-chapel-schools.htm. Accessed 23 Jan. 2025.

Scott, Joan Wallach. “The Movement for Reparations for Slavery in the United States.” In the Name of History, Central European University Press, 2020, pp. 61–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv16f6cq3.6. Accessed 22 Jan. 2025.